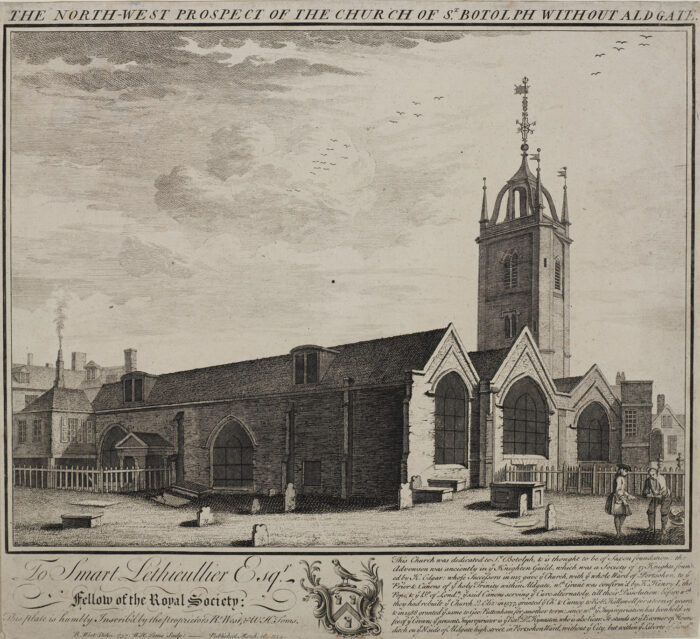

While the church which stood on this site from the 1500s may have survived the Fire unscathed, by 1711 the parish was keen to see it replaced. The rector, the Revd Thomas Bray, along with the churchwardens and vestry, petitioned the government for both a new church and minister’s house to be built in the East Smithfield district of the parish.

They argued that it was needed to serve the population of some 9,000 inhabitants, of which two thirds were too poor to pay local taxes. The case to build 50 new churches was not deemed a priority by the commission, and in any case, it ran out of money before it could fulfil its original objective.