St Vedast

Read the stories of four that either survived or succumbed to the flames, and how they reemerged from the ruins.

St Vedast

Joshua Gee was a well-known and prosperous Quaker. Alongside generous bequests to his children he also left money to the Quaker Workhouse in Clerkenwell. The family attended the Peel Court Meeting House off St John Street nearby, and used the Dissenters’ Burial Ground at Bunhill Fields.

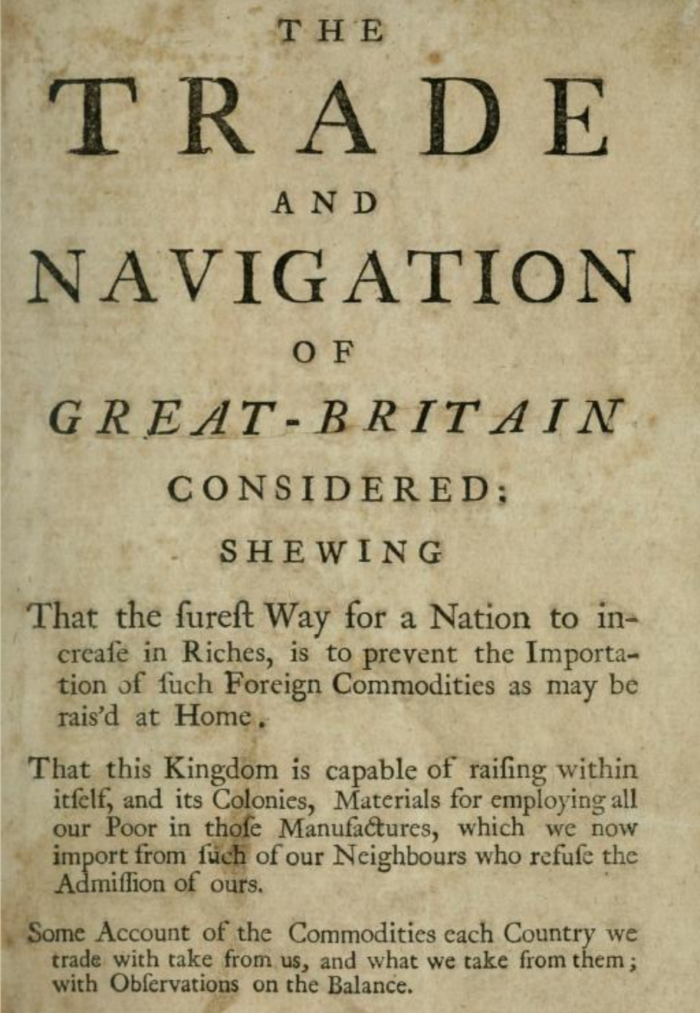

'The trade and navigation of Great-Britain considered: shewing that the surest way for a nation to increase in riches, is to prevent the importation of such foreign commodities as may be reais'd at home ...' 1729 by Joshua Gee

He became a Master of the Grocers’ Company by purchase, without serving an apprenticeship. He himself had seven apprentices between the years 1693 and 1718, including his son John. All boys were from Quaker families, most from London, but one from Bristol. In general, they seem to have prospered. On 17 December 1718 Joshua was appointed a Governor of Bridewell Hospital.

Joshua Gee held firm views about economics, and in 1729 published a popular work ‘The Trade and Navigation of Great Britain Consider’d’. In it he highlighted labour shortages in the colonies, and advocated for the transportation of convicts, the poor, and unemployed to boost the labour force in Virginia and Maryland.

In 1715 Joshua founded the Principio Company with Augustine Washington, father of George. This Company shipped pig and bar iron from Maryland and Virginia to Britain. In 1708, with a group of eight others, he assisted William Penn in raising money to pay debts by granting him a mortgage on his Pennsylvania estate. At home, he advised the Board of Trade and Plantations.

On the night of 29 May 1715, however, Joshua found that Cheapside was a dangerous place to be. He was caught up in a disturbance of up to a hundred men fuelled by drink, armed with sticks and looking for targets.

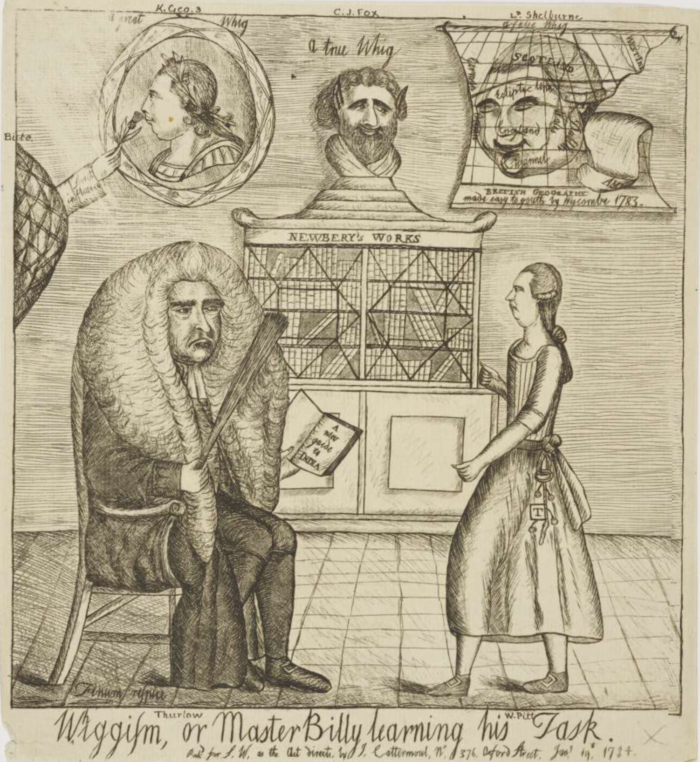

'Whiggism, or Master Billy learning his task.' © The Trustees of the British Museum

As a Quaker, Joshua was suspected of Whig sympathies and was lucky to get away with some jostling, being struck in the face, and having his hat knocked from his head. His servant Jardin protected him to an extent. The mob moved along Cheapside, into the parish of St Vedast alias Foster. In Foster Lane they apparently confronted the constables, hissing at them as a sign of aggression and disapproval. Some of the mob moved into Carey Lane where apprentices, who were generally eager for trouble-making, lit a bonfire. The date was significant as the anniversary of the Restoration. The mob shouted: “No Hanoverian, no Presbyterian, High Church forever, a second Restoration, No King George but James III.”

This particular riot was one in a series of mob outbreaks this year. Only the previous day, 28 May, there had been large demonstrations in Smithfield, Highgate and a particularly violent show of force at the Stocks Market near Walbrook. Being close to Cheapside, this must have spread alarm. Before that, on 23 April , a mob had gathered at Snow Hill, off Holborn, to mark the anniversary of the late Queen Anne’s death. They lit celebratory bonfires and waved a banner proclaiming Anne as “just and good”. Windows left unlit for the celebration were broken at St Andrew’s, Holborn. Quakers were one of the groups used to being singled out as legitimate targets of violence. For example, in the so-called Sacheverall riots of 1710, the Meeting House in Lincoln’s Inn Fields was attacked and destroyed after Henry Sacheverall preached a lengthy sermon denouncing Dissenters as ‘false brethren’ as he called for unity in both Church and State.

Read more about Difference, Discrimination and Violence.

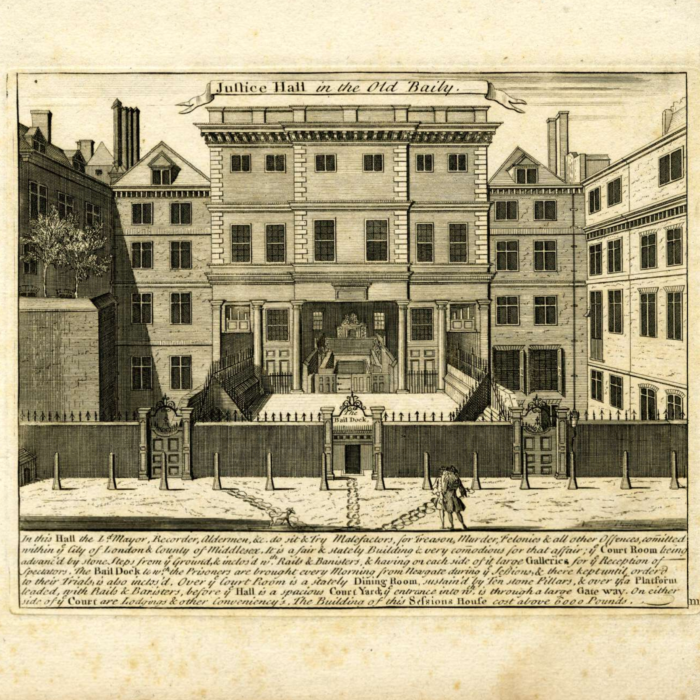

'Justice Hall in the Old Baily', 1734-4 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Seven of the Cheapside 29 May rioters were tried at the Old Bailey on 13 July 1715, charged with the misdemeanour of breaking the peace and, much more seriously, with riot.

Witnesses identified the seven, all of whom were from the parish of St Mary le Bow. Cordwainer and constable of Cordwainer Ward, Abraham Hazard of Bow Lane, gave evidence against Thomas Harvey, having seen him go down Foster Lane abusing the constables.

A concerned householder, who had called for the constables to protect his property after fleeing his house in a nightgown, identified Richard Cannon. Gee’s servant Jardin identified Thomas Rye as the man who had attacked his master, supported by Mr Low who had seen him two doors away from Gee’s home.

Some of the accused gave alibis, or had their employers speak to their good character. Rye admitted to knocking off Gee’s hat, but denied striking him. The seven were found guilty of riot. However, sentencing was delayed and somewhat surprisingly, they were released unpunished.

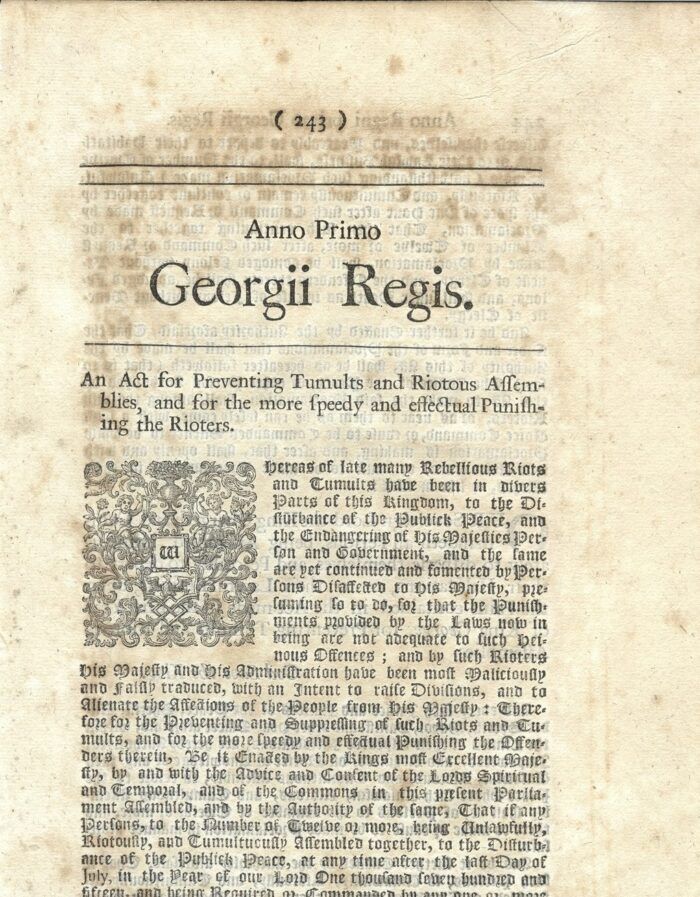

First page of the Riot Act 1714, first edition, 1715, London, Jay Dillon Rare Books.

Britain was becoming tired of the “many rebellious riots and tumults”, as described in the London Gazette, taking place all over the country. “An Act for preventing tumults and riotous assemblies, and for the more speedy and effectual punishing the rioters”, came into force on 1 August 1715. The Riot Act was not repealed until 1973. The Riot Act could be “read” out to gathering crowds to advise them to disperse. Law officers were in effect permitted to use even lethal force against rioters who failed to disperse after an hour, and convicted rioters could be charged with a felony and face the death penalty. Would Joshua Gee have preferred to have those convicts transported to the Colonies?

Read the stories of four that either survived or succumbed to the flames, and how they reemerged from the ruins.

Keep up to date with the latest news ...