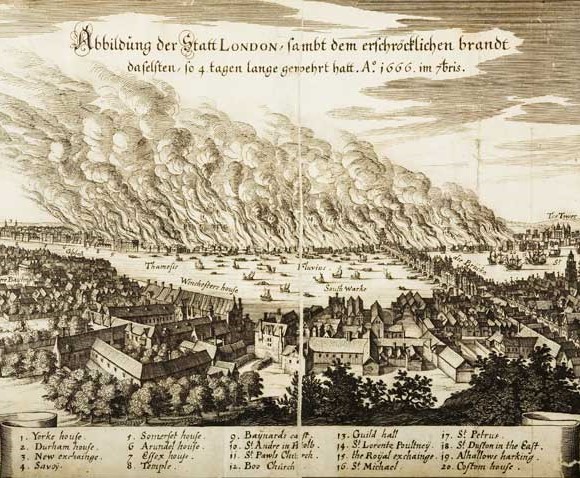

Following the Great Fire, leaders and businessmen had to find huge amounts of money to fund the rebuilding of the City.

Rebuilding the city after the Great Fire was both an urgent and colossal task. One-third – 436 acres – of London had been destroyed, including over 1300 houses and making 100,000 people homeless.

The medieval City had to be totally reconstructed – houses, shops, public buildings and infrastructure – and quickly, presenting a monumental financial challenge. The Corporation of London, the governing body of the City of London, raised money by putting a tax on one of the capital’s most widely-needed and valuable commodities: coal.

Image: View of the Great Fire of London taken from Southwark, Matthaus Merian the Younger, 1670 © London Fire Brigade

Stuart London was a coal-fired city, using vast amounts of ‘sea coal’, shipped largely from Newcastle, for both domestical and industrial processes. It heated homes, businesses and water and fuelled the furnaces of all sorts of manufacturing processes – brick and glass-making, brewing and baking, smelting metals and refining sugar. It is estimated that one ton of coal was consumed each year for every resident of the City. It was a necessity of life and a prime source of revenue. But London’s voracious need for coal also lead to it being one of the most polluted cities in the world.

Read more about Pollution and Plants.

A year after the fire in 1667 Parliament passed a Rebuilding Act which increased the duty to be paid on coal entering the Port of London. The money raised was divided between rebuilding some of the 87 out of 109 parish churches that had been destroyed churches, City of London property, such as the Guildhall, markets, prisons and other civic buildings, and a new St Paul’s Cathedral to rise again out of the ashes.

Rebuilding on this scale required large sums of money to be readily available – to invest in buildings, to buy materials, and to pay architects, workers and craftsmen. Many new banking firms were established in the Square Mile at this time and played a key role in facilitating the rebuilding. Banks helped provide the capital investment needed, lending money, as well as handling the financial transactions to pay for the works. With so much work being commissioned, craftsmen and traders made use of local banks to deposit their income and to withdraw money for supplies and workers’ wages.

Hoare's Bank sign of the Golden Bottle still used today.

Hoare’s Bank was particularly successful. It was located in Fleet Street at the sign of the Golden Bottle. There were no street numbers at this time and so large, overhanging signboards in the shape of a distinctive object, helped customers (especially if you couldn’t read) to recognize a business’s address.

Learn more about Signs of the Times.

Amongst Hoare’s customers was mason Samuel Fulkes who made weekly withdrawals from it to pay his team, amounting to nearly £8,000 (£840,000 today) over sixteen years.

With so much work being commissioned, craftsmen and traders made use of local banks to deposit their income and to withdraw money for supplies and workers’ wages. Amongst Hoare’s customers was mason Samuel Fulkes who made weekly withdrawals from it to pay his team, amounting to nearly £8,000 (£840,000 today) over sixteen years.

Not only could you profit from being directly involved in the rebuilding works but also from investing money in them and providing loans to fund new buildings and businesses. In the late 1680s for example, investors could even make money by lending towards constructing the new St Paul’s Cathedral at a rate of 5-6%. A very lucrative return!

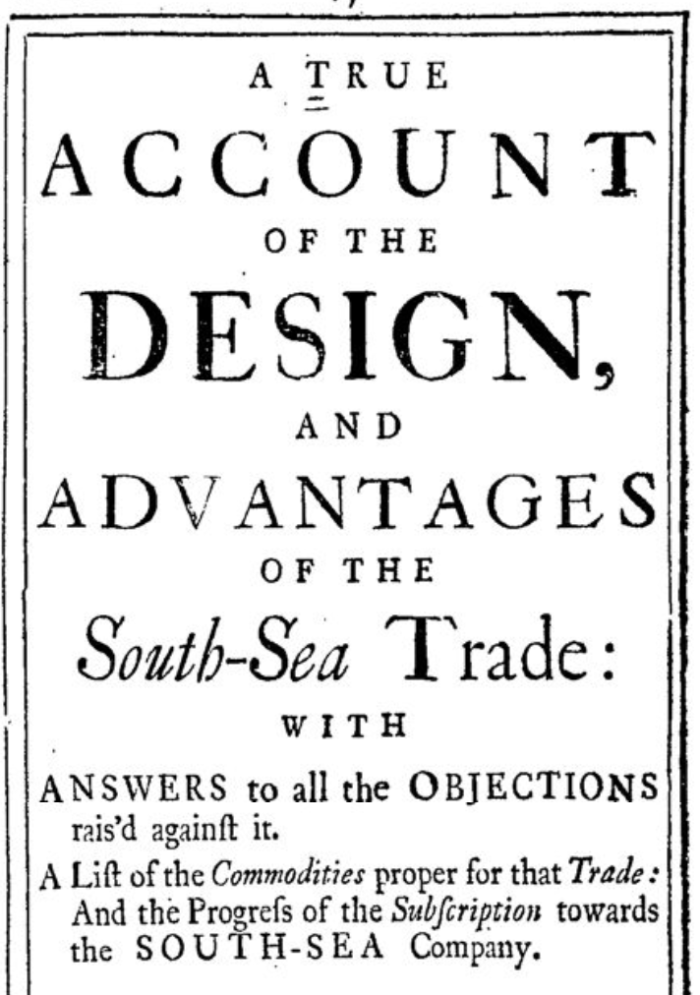

A true account of the design, and advantages of the South-Sea trade ; with answers to all the objections rais'd against it : a list of the commodities proper for that trade : and the progress of the subscription towards the South-Sea Company, 1711, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, Harvard University.

There is also a more troubling side to the capital investment needed for all the rebuilding. Profits made from overseas investments – including the slave trade – helped fund the mammoth costs involved and were channelled into rebuilding the City by both wealthy investors and benefactors.

Pamphlet attributed to Daniel Defoe outlining the ‘mighty advantage to the kingdom and an everlasting honour to the present parliament’ arising from the company’s trade monopoly with Spanish colonies in South America.

Read more about The South Sea Company and the Slave Trade.

Thousands of ordinary people, as well as banks, bankers, and the Church of England, bought shares in companies like the Royal African Company and the South Sea Company, which was granted the control of trafficking captured and enslaved Africans to the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in South America.

The owner of Hoare’s Bank, Henry Hoare, made a profit of £28,000 from selling stocks in the company – the equivalent of nearly three million pounds today.

Learn more about Enslavement and Migration and Wren’s Commercial Interests.

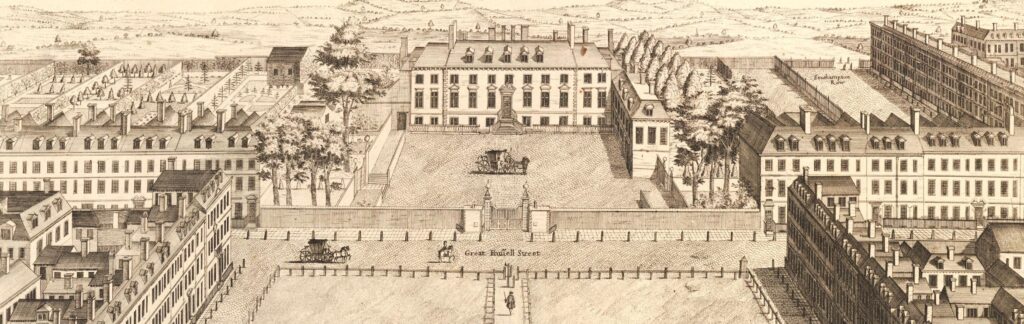

Building after the Fire was, however, not just confined to replacing burnt properties. A building boom followed as speculative developers built new streets, squares and fashionable terraced housing developments beyond the Square Mile to the west and north of the City. London’s population expanded outside of the city walls as new residential suburbs were created.

St Bride’s parishioner, physician and economist Nicholas Barbon was one of the most prominent developers of this period. He began his property career by rebuilding his father’s premises in Fleet Street. He built nearby Crane Court and lived in one of the houses with his wife Margaret. Sadly, his son John was buried at St Bride’s only a few days after he was christened there. The renowned diarist Samuel Pepys – who had been born in Salisbury Court in the parish of St Bride’s – moved to another of Barbon’s new developments, Buckingham Street in 1679.

Read more about Dr. Barbon’s speculative property career and housing developments – not always to the highest standards – at the Garden’s Trust’s blog.

Several church craftsmen also invested the profits from their trade into building new housing stock and communities. Carpenter John Longland, for instance, was involved in residential developments, such as Hatton Garden, which was laid out in 1659. He leased a house and adjoining building yard in Great Kirby Street, and joiner Valentine Houseman also moved into the area.

Read the stories of four that either survived or succumbed to the flames, and how they reemerged from the ruins.

Keep up to date with the latest news ...