Read the stories of four that either survived or succumbed to the flames, and how they reemerged from the ruins.

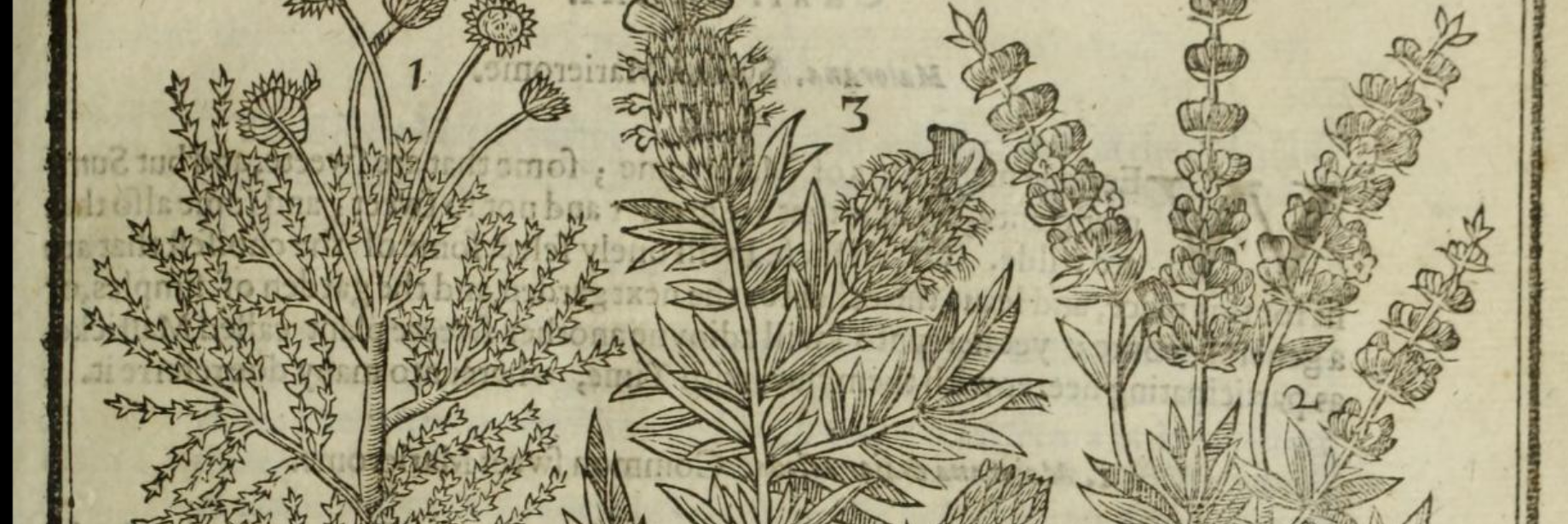

Not only were herbs important but other plant material too. Sedge, a grasslike plant, was strewn on the floors of domestic and public chambers to keep down the dust and mask smells of cooking, food waste, privies and unwashed people. Flowers were scattered on tables of the rich before a meal, and some were even eaten. According to church records, bay and rosemary were used in burials as well.

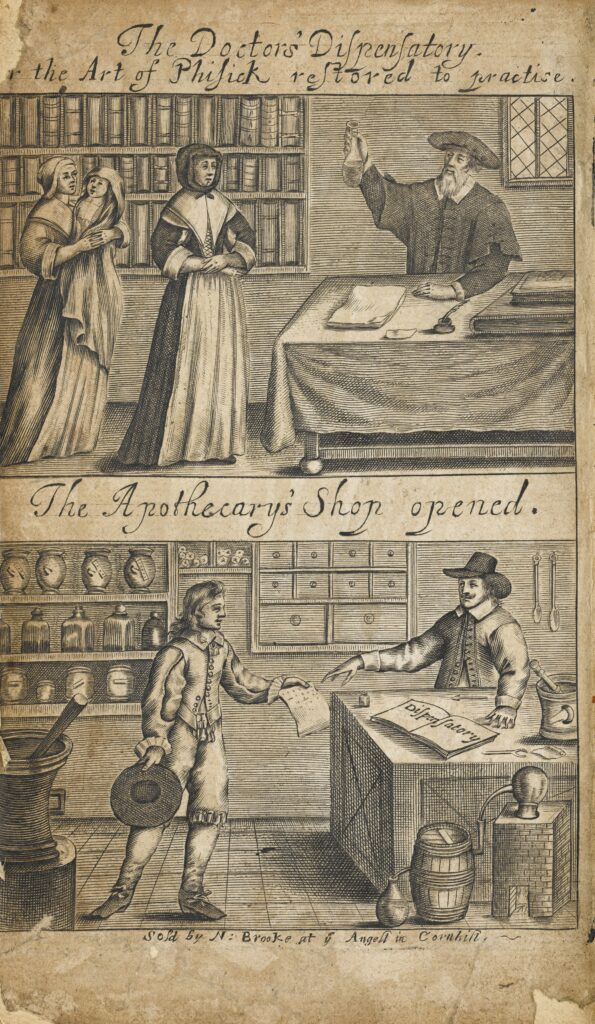

In seventeenth-century England doctors were few. Their treatments were expensive and not usually effective in curing deadly diseases. The bubonic plague, also known as the Black Death, and smallpox were constant threats, and killed thousands of people. The year before the Fire of London, the Great Plague killed about 100,000 people or one-fifth of London’s population.

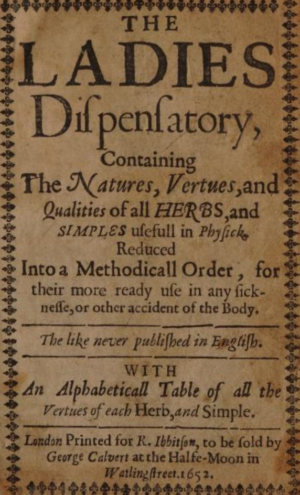

Both apothecaries (a type of chemist in the past who made and sold medicines) and housewives who cared for the health of their families, relied on many different types of medicinal herbs and their healing properties to treat all sorts of ailments, serious and minor.

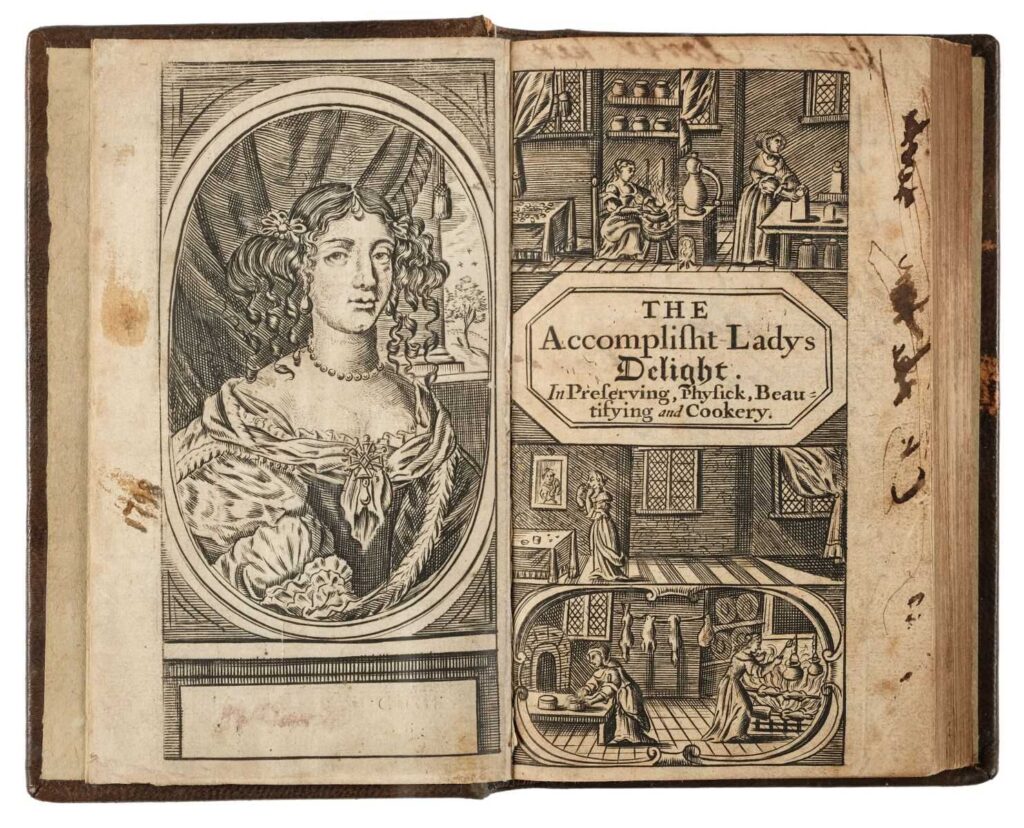

Women would turn to recipes passed down from one generation to another, or published household manuals containing instructions and ingredients for every type of domestic need, whether health, hygiene, beautification or cookery. Botanical-based remedies – elixirs, balms and distillations – were used to cure anything from a cough to cancer, gout to stomach-ache… even the bite of a mad dog.

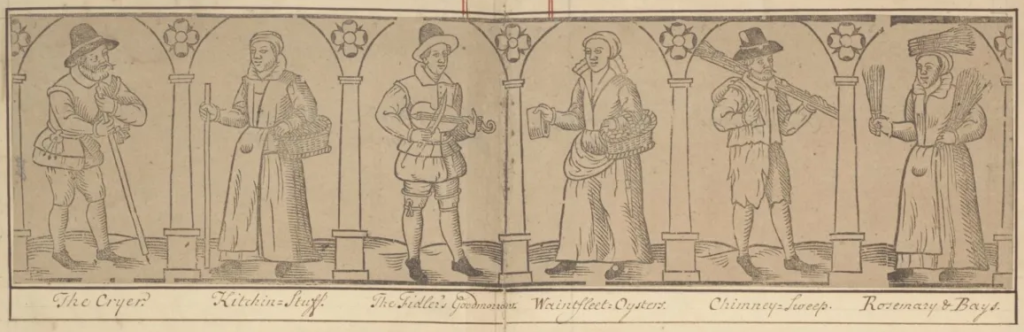

If however, you didn’t have a kitchen garden where you could grow your own flowers and herbs, or if it just didn’t produce what you needed, then you could turn as Gideon Harvey, physician and author, recommended in the 1670s, to the “physical herb women” who could supply you with herbs at the London markets for half a penny a handful.

Find out more about London herbs by Margaret Willes.

Gathering herbs and selling them in markets and on the streets was a long-established London trade that was almost exclusively carried out by women. They gathered wild herbs from the countryside such as Hampstead, or grew them on plots of land outside the City. The herb market near St Paul’s Cathedral was destroyed in the Fire as well as other street stands, but better stalls were provided in the four new markets.

We know the names of several herb women: Mary Merry at St Georges Church, Hanna Smith in Grub St and Bridget Rumney who for eleven years from 1660 held the appointment of ‘Herb Strewer to the King’, helping mask the foul odours that even palaces harboured. Bridget’s annual pay was £24 plus two yards of scarlet cloth for her livery.

Read the stories of four that either survived or succumbed to the flames, and how they reemerged from the ruins.

Keep up to date with the latest news ...