Read the stories of four that either survived or succumbed to the flames, and how they reemerged from the ruins.

John Evelyn, diarist and environmentalist, wrote passionately about the poor air quality in London in the 1660s. People had coughs all the time and half the deaths were caused by lung disease. The problem came from burning the sea-coal shipped from Newcastle. John recalled:

The aer is eclipsed with a cloud of sulphur as the Sun it self … is hardly able to penetrate, it produces a sooty crust or furr upon all that it lights upon. It kills our flowers and bees abroad

The churches and other fine buildings were blackened. It was not the household culinary fires but from the brewers, dyers, lime burners, salt and soap boilers. He argued that they should be moved six miles out of London but anticipated that the “avarice of men in this age” would prevent this from happening. Ironically it was the profitable coal markets which funded the rebuilding of the City.

John Evelyn proposed large plantations to encircle the east and south west of the city with trees and shrubs ‘that yield the most fragrant and odoriferous flowers….sweet briar, woodbinds, white and yellow jasmine, lavender and above all rosemary’.

While this vision was sadly not realised, public enthusiasm to have plants and flowers in domestic and commercial buildings to beautify the city and clean the air was widespread. The new Woolchurch Market, for example, had lime trees planted all around it.

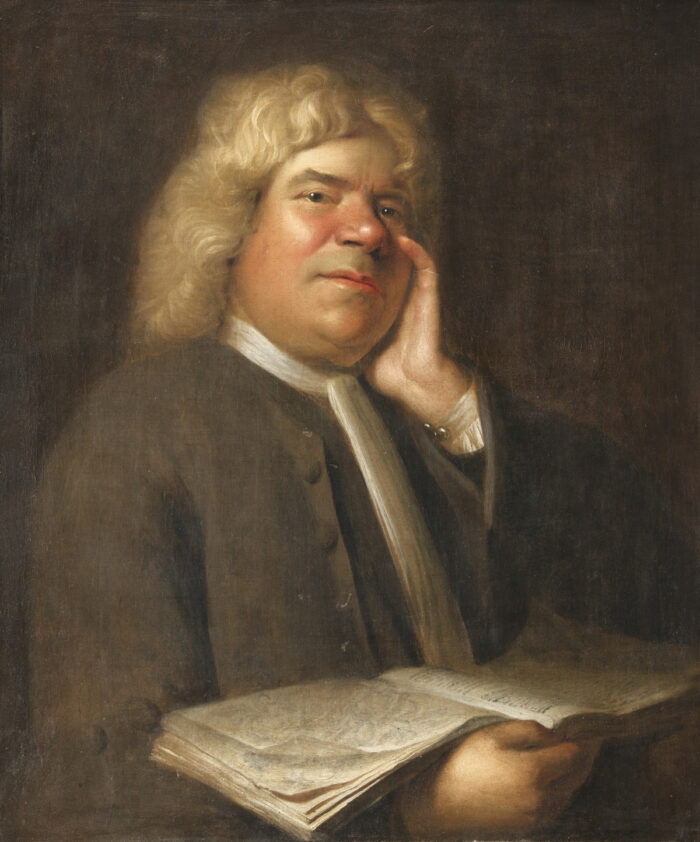

Thomas Fairchild (1667—1729), Department of Plant Sciences, University of Oxford

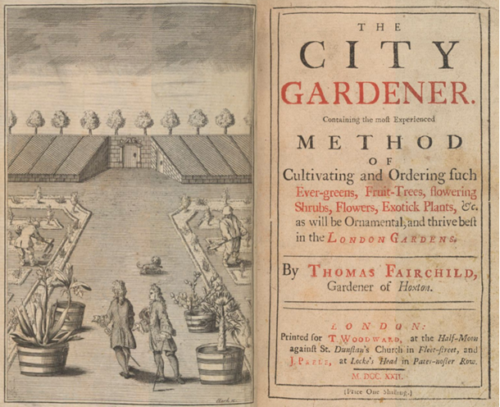

Thomas Fairchild, a nurseryman from Hackney, wrote his book The City Gardener (1720), in which he proposed that the new squares, if planted in the wilderness style, would be a harbour for birds and walks through the public squares would give shade and privacy.

Fairchild understood the pleasure that all people, not just those of ‘quality’, could get from their gardens and having potted plants around them in their houses. He wrote that he had made it his business to consult “what plants will live even in the worst air of chimneys and the most pent-up air we know.”

He noted that plants which flourished included pink and white lilacs, laburnum, white jasmine, while elder trees, vines, fig trees and Virginia creeper could all thrive, even with little sun. Fairchild even offered a seasonal solution: indoor plants such as ‘a pyramid of Orange trees intermixed with Mirtles and Aloes displayed in Delph Ware dishes’ were supplied by his nursery when in bloom and returned ‘to his care for the winter for the usual price.’

Read more about Thomas Fairchild and London Nurseries at the Gardens Trust.

Read the stories of four that either survived or succumbed to the flames, and how they reemerged from the ruins.

Keep up to date with the latest news ...